In 1832, the same year Matthias Baldwin built his first locomotive, construction of the first Wills Eye Hospital was begun at 18th and Race Streets in Philadelphia. James Wills Sr. (1748-1823) immigrated from England at a young age and was employed as a coachman and as a huckster. He married Hannah Roberts in 1774. Wills Sr. accumulated a fund of $10 to start a grocery business at 84 Chestnut Street by 1785. In 1787 he bought the building from Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush for 700 pounds. He, his wife, and their only child lived above the store. Over time he bought the houses on either side of the store and added some outbuildings. James Wills Jr. (1777-1825) eventually joined his father in the grocery business. The mother died of tuberculosis at age 74 in 1813, and the father died in 1823 at age 75. James Jr. died two years later. The son was unmarried with no children, so he spread his estate over several charities.

This article will discuss the first and second Wills Eye Hospitals, the former just outside our neighborhood and the second within our neighborhood and still standing. The second less conspicuous name on the second hospital will be discussed. And since we are on the topic of big-W Wills, I will also discuss some relevant neighborhood little-w wills.

Th partnership between Turnbull and Wills was announced in June of 1821 in The National Gazette, a Philadelphia newspaper, and dissolved in September of 1821 with this announcement in the same paper. Other than this brief enterprise, the Wills grocery was a family affair.

James Wills Jr. is the person associated with Wills Eye Hospital, but a claim can be made that it was James Wills Sr. who should have that honor. The father signed his will on April 24, 1823, and he died eight days later of what sounds like congestive heart failure. The son signed his own will two weeks later, on May 8, 1823 (see text summary of will here.)

The son died January 22, 1825. In an article in The Columbian Observer, on February 1, 1825 the father and son are both remembered, and writing of the father it is noted “…when he died, he left to his son most of his property, 150,000 dollars… with an injunction, that should his son have no children, he would so dispose of it, and he particularly enjoined him to found a Hospital for the Lame and Blind. With the desire of his worthy father, the son leaving neither wife nor children, has strictly complied.” Thus it would seem that the money that funded the hospital, and the very idea of the hospital, belonged to the father, with the son fulfilling the wishes of the father. It may also be that the explicit instructions in the son’s will to include his surname in the hospital name may be in tribute to his father. This would probably soften the charge that was levelled against the son in the February 27, 1825 edition of the Columbian Observer: “The objects of his bequest are certainly laudable; but who can imagine in such a breast resided the lust for fame.” Talk about biting the hand that feeds you!

We are all familiar today with “naming rights” for any structure, whether college, hospital, research center, entertainment venue, or athletic stadium. A recent Philadelphia philanthropist even reneged on a $2 million donation to a religious school because the school would not rename the school for him. Stephen Girard (1750-1831), who signed his will in 1830 and died in 1832, bequeathed most of his estate to fund a college for “poor, white, male, orphans,” but did not specify the name of the orphanage. He also left smaller bequests to local charitable institutions (see Girard's 30-page will here) including some of the same institutions mentioned in the will of James Wills Jr. The 1835 will of Jonas Preston (1764-1836) also did not mention the name for the maternity hospital in his bequest (his 8-page is here) although it was named the Preston Retreat on completion.

Wills died unattended in 1825 at age 48, with cause of death listed as obesity. No likeness of Wills exists. The signer of this document, Quaker Dr. Joseph Parrish, was Wills’ friend and physician, and would become the first president of the board of the Wills Hospital.

The summary of the will of James Wills Jr. as published in The Philadelphia Inquirer on January 26, 1825. The residuary estate of $70,000 would be inflation-adjusted to $2.5 million today. By the time his hospital was built in 1832, the estate had grown to $122,000.

The Friends Asylum was established overlooking Tacony Creek in Northeast Philadelphia in 1813 and still operates as Friends Hospital at that location. James Wills was a member of the Society of Friends (i.e. a Quaker). The Wills family had been admitted to the Philadelphia Friends’ Meeting in 1802.

The other charities in his will had connections to the new hospital of James Wills and to this neighborhood via proximity. The Philadelphia Society for the Establishment and Support of Charity Schools was a private charity chartered in 1801 that provided free education in the days before tax-supported public schooling. Once public schools were widely utilized, the Philadelphia Society stopped holding classes in 1890, although free public lectures were continued at the Academy of Natural Sciences at 19th and Race Streets, across 19th Street from the first Wills Eye Hospital.

The Magdalen Society had erected a building to house “fallen women” at the northeast corner of 21st and Race Streets in 1808. Most of this complex was demolished in 1916 and is now the empty land on the west side of the Franklin Institute property. For more on the Magdalen Society see outside link here.

The Orphan Society (see outside link here) was established in 1816 and in 1818 built its orphanage at 18th and Cherry Street. The first Wills Eye Institute would be built on the block next to the orphanage.

Dispensaries were basically free outpatient medical clinics for the poor and were scattered throughout the City. There was a free dispensary, Charity Hospital, at 1832 Hamilton Street, after the Civil War, in what is now Matthias Baldwin Park.

It should be noted that there were other hospitals specializing in care of the eye prior to 1825. Even within Philadelphia, Wills Eye Hospital was not the first. In 1821 George McClellan, father of the future Civil War general, had opened the Dispensary for Diseases of the Eye modeled on newly opened facilities in New York City. In 1823 the name of the dispensary was changed to the Philadelphia Hospital for Diseases of the Eye and Ear. Eye diseases like cataracts were surgically treated for all, without regard to ability to pay. McClellan seems to have become distracted by his founding of the Jefferson Medical College in 1825, since after that year there can be found no mention of his eye hospital. Perhaps it was into this void that James Wills Jr. saw a need and opportunity.

Portion from an 1860 map (here) showing the area around Wills Hospital. North is to the right.

East of Wills is the Orphan Asylum, labeled simply "Asylum," and to its west is the Magdalene Asylum and the Blind Asylum. The cruciate building labeled "Foster Home" is the Preston Retreat. Neighborhood manufacturers like Norris Locomotive, Baldwin Locomotive, and Asa Whitney's Car Wheel Works are also shown.

A postcard from here depicting the 70-bed hospital which opened in 1833 at 18th and Race Streets as The Wills Hospital for the Indigent Blind and Lame. The name on the building is Wills Eye Hospital. When another story was added in 1908, the new name on the building became Wills Eye, and this would also be applied to the second hospital building on Spring Garden Street.

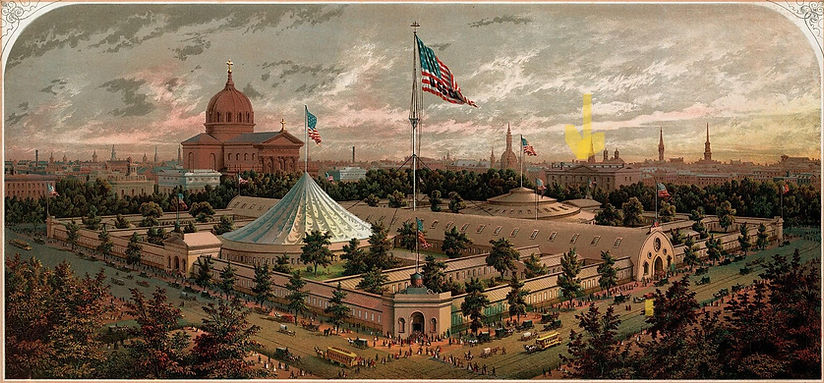

Famous chromolithograph from here of the June 1864 Central Sanitary Fair at Logan Square to raise money for the Union troops. Wills Eye Hospital is under the yellow arrow. The view is looking southeast from the corner of 20th and Vine Streets. The just completed Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul is the dominant building in this image.

The hospital grounds and building would occupy the whole block between 18th and 19th and between Race and Cherry Streets. Wills Eye would be the only building on the streets facing Logan Square in 1832. At that time the square was used for pasturage and public hangings, the last hanging being in 1823 as described in our article here. The hospital lot had been purchased for $20,000 and the building itself would end up costing $57,000. The hospital was designed by Thomas Ustick Walter, who designed Girard College Founder’s Hall (cornerstone 1833) one mile north of Wills Eye, and also the Preston Retreat (cornerstone 1837) a few blocks north at 20th and Hamilton Streets. Preston left his estate to the State of Pennsylvania; Girard and Wills to the City of Philadelphia. In 1869, the Pennsylvania legislature established the Board of Directors of City Trusts for the purpose of administering all funds left in trust to the City of Philadelphia, including that of James Wills and Girard.

Why the explicit combination of “blind and lame?” James Wills was a Quaker who knew his scriptures. He was also probably quite aware of the Benjamin West painting unveiled at Pennsylvania Hospital in 1817. The painting, Christ Healing the Sick in the Temple, is based on the Biblical passage: “And great multitudes came unto him, having with them those that were lame, blind, dumb, maimed, and many others; and cast them down at Jesus’ feet; and He healed them.”

Benjamin West painting of Christ Healing the Blind and Lame. Grand paintings like this would be viewable by the public for a fee, in 1817 that fee being 25 cents (ten dollars for a lifetime pass). The painting with its life-size figures is still at Pennsylvania Hospital.

Pennsylvania Institution for the Instruction of the Blind in a lithograph from 1838. Another wing on each end of the building would be added by the 1860s.

James Wills would probably have left a bequest to the Pennsylvania Institution for the Instruction of the Blind if it had been built prior to his death. It ended up situated one block from the hospital that would bear his name. The institution was founded in 1833 and was at the northeast corner of 20th and Race Streets for 65 years, when it moved to Overbrook. The Magdalen Society mentioned in the will of James Wills was just behind this building. The site of both is now occupied by the Franklin Institute. All told there were several buildings located near Logan Square with connections to James Wills in 1833.

In the early 19th century disease and injuries to the eye were treated by general practice doctors. Gradually physicians were specializing in the eye alone, and Wills Eye became the first US hospital specializing in care of the eye. In the days of untreated gonorrheal disease of the newborn eyes, of untreated cataracts and glaucoma, and of pre-OSHA industrial eye accidents, there was a lot of chronic eye pathology and blindness. Matthias Baldwin had moved his larger factory to the neighborhood in 1835, and would be joined by other metal workers in the area, aggregating over 20,000 factory workers in the neighborhood. At Wills Eye Hospital care of these patients took precedence, but ophthalmology training and research was gradually folded into the mission of the hospital. The original hospital was expanded both vertically and laterally in 1909, with designs by John T. Windrim, but still could not meet the needs of the patient volume.

Eye surgery circa 1910 at Wills Eye Hospital.

Ocular antisepsis was introduced in 1881, but surgeons continued operating without masks and gloves into the 1950s.

Just as one example of the pioneering research done at Wills:

Cataracts had been treated surgically since the eighteenth century, using one of three methods: displacement below the pupil; fracturing and leaving in place to be absorbed slowly within the eye; or extraction. Wills' physicians developed ultrasonic breakup of the cataract with removal and also intraocular lens replacement, which are the current practices.

Around 1930 a lot measuring 198 by 171 feet was purchased for $292,000 at the northwest corner of 16th and Spring Garden Streets. A new 120-bed hospital was built in 1932 with designs by busy Philadelphia architect John T. Windrim, who between 1932 and 1934 also designed in our neighborhood the Family Court Building at 1801 Vine Street and the Franklin Institute. The new hospital was placed on the National and the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places in 1984. See here for the architectural details in the National Register of Historic Places nomination form.

So what happened to the first Wills Eye Hospital on Logan Square?

Publisher Cyrus Curtis and family were staunch supporters of the music scene in the city and wanted to place a new concert hall on the Parkway to replace the dated Academy of Music. Curtis purchased the Wills Eye Hospital and an adjoining property in 1930 for $2 million and along with Eli Kirk Price began a fundraising campaign to complete the project. Architectural drawings were completed by the New York firm of Voorhees, Gmelin, and Walker in 1932. The financial collapse in the depression, and the deaths of Curtis and Price in 1933, put an end to the project. The building was used as the juvenile court from 1934 to 1938 and demolished in 1944.

The 1932 drawings for the proposed concert hall. The rest of the Parkway buildings on and west of Logan Circle up to that date had a neoclassical style reminiscent of the Court of Honor plaza at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Photo credit here.

Back to the second Wills Eye Hospital...

Here are a few photos and maps of the 1601 Spring Garden Street site over the years:

Portion of an 1858 map

16th Street runs vertically on the right

Portion of a 1917 Sanborn map. 16th Street runs vertically on the right.

A smelting works might seem unusual next to a public high school, but even in 1917 our neighborhood still had active metal works at Baldwin, Bement, Sellers, and across the street at the third Mint. The Mint was built in our neighborhood in 1901 for two reasons: there was space, and a minting plant is basically a metal shop, and this was the neighborhood to be in. The Automobile repair shop and school on this map replaced the Kramer furniture factory on that corner after over a decade of fine furniture making there.

The Wills Eye site in 1919 looking east from Girls' High School

Portion of an aerial photo from 1928 (photo credit Library Company of Philadelphia). Girls High School is the five-story building on the left. The Girls High School Annex is just to the east of the main building. Auto repair shops and gas pumps take up the rest of the block to the east.

Ad from The Philadelphia Inquirer of August 29, 1920, page 58.

Automotive businesses were big in the neighborhood and along North Broad Street at this time. The Louis Bergdoll Motor Company was two blocks south, at 1600 Callowhill Street, in our neighborhood.

The new Wills Eye Hospital upon completion in 1932

The first floor had a large lobby and administrative offices. The mezzanine had clinics and seven resident’s rooms (the medical residents being in residence full time in those days). The third floor had the children’s ward and two wards for inflammatory conditions. Cataracts were common. There were two cataract wards of 29 beds each on the fourth floor, along with an operating room. The fifth floor had private rooms for the paying patients. The nurses’ quarters were on the setback sixth floor. A penthouse apartment for the hospital superintendent was above that.

There are two dates flanking the words Wills Hospital above the entrance: 1832, the year of the founding of Wills Eye Hospital; and 1932, the date of the cornerstone of the second hospital. For this reason it is sometimes referred to as the Centennial Building.

1938 aerial view looking northeast. The 1600 block of Spring Garden Street is on the lower left, with Philadelphia Girls High School to the west of Wills Eye Hospital and the 3rd United States Mint across the street. The photo shows the land after the removal of the empty Baldwin Locomotive Works buildings.

The first Wills Eye Hospital near its end is in the lower right side of this 1932 photo, taken from the top of the new Free Library building. The third-floor addition on Wills Eye, completed in 1908, can be seen. The vacated first Wills Eye building was used for several years as a branch of the Municipal Court from 1934 to 1938 and demolished in 1944. The Parkway Family Court building was finished in 1941. The former Wills lot would provide surface parking for decades.

A surface parking lot is still there in 1966. Cyrus H. K. Curtis, the Philadelphia publishing magnate, had bought the first Wills Eye building in 1930 for $1.1 million, plus some adjacent land. His plan to build a concert hall on the Parkway never panned out. The $145 million One Logan Square office building and Four Seasons Hotel was completed in 1983. It is now the Logan Hotel.

After World War II the research work at Wills outgrew the basement labs at 1601 Spring Garden Street. A dilapidated building on Brandywine Street behind the hospital was purchased for $3,000 and refurbished in 1952 for use as the first Wills Eye Research building.

The Wills Hospital Research Building at 1603 Brandywine Street. A dilapidated building at 1601-03 Brandywine Street was purchased for $3,000 and remodeled. In 1959 a new research building at 1605-1609 Brandywine was constructed. The 1959 building was designed by architect Vincent Kling and its construction included the first use of now-ubiquitous metal curtain walls on a building in Philadelphia. The east and west faces were conventional brick; the orange-red metal curtain walls were installed on the north and south faces where there was adequate distance from other structures. The building on the left in the distance is the still-extant 1601 Green Street. Wills sold its holdings on Brandywine Street in 1993 and this site became townhouses.

Image taken from a 1966 revised Sanborn map at the Parkway Central Library shows the original research building at 1603 Brandywine Street (1601 has been demolished by 1966) and the new bespoke building at 1605-1609.

The Sanborn map books were really a subscription service. When revisions were to be made to the original 1917 map, the Sanborn folks would stop by the library and pick up the bound volumes for cut-and-paste revisions to be made in New York City.

This is a portion of the map from 1978 of the boundaries (bold lines) of the nominated and approved Spring Garden Historic District. The original and new research buildings of Wills Eye can be seen fronting Brandywine Street, and the parking lot is to the north. The research buildings were demolished and replaced with large brick townhouses fronting Brandywine and Green Street in 2007.

In 1972 Wills Eye became affiliated with Jefferson Medical College and in 1980 moved to a new hospital building at 9th and Walnut Streets next to Jefferson.

The third Wills Eye, and its state historical marker, at 9th and Walnut Streets.

Unlike the first Wills Eye Hospital, the Centennial Building survives as a condominium complex called The Colonnade. There are 115 units, ranging from studios to two bedrooms.

Lobby entrance with double staircases to the mezzanine in the Colonnade.

Floor plan of one of the six floors at The Colonnade

I said in the introduction to this article that there are two names on this building. The second name on the west side marks the entrance for what was the Bushrod W. James Eye and Ear Institute.

Bushrod Washington James (1836-1903) was the great-great-great grandson of David James, who travelled to Pennsylvania from Wales on the same ship as William Penn in 1682. His father and grandfather were both Philadelphia physicians, his father being one of the pioneers of homeopathy here. In 1857 Bushrod graduated from the Homeopathic Medical College of Pennsylvania (the precursor to Hahnemann Medical College) and set up an infirmary at the northeast corner of 19th and Wallace Streets (now a ball field) while residing at 1719 Green Street. He devoted time to many medical, educational, and charitable organizations. Like James Wills, he never married. At his death of pneumonia in 1903 he left the City of Philadelphia houses and personal effects, as well as two endowments: $40,000 to establish a library in his home in the Logan Square neighborhood; and $55,000 to fund an eye and ear institute (see New York Times article here). Decades after his death, the City trustees determined that the library would be built in the Oxford Circle neighborhood as the Bushrod Branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia (for its history see outside link here). It opened in 1950. Only 16 of the 54 neighborhood libraries are named for famous Philadelphians, the Bushrod Branch being the only one bearing solely a first name. The eye and ear institute was incorporated into the Wills Eye Hospital. For more childless philanthropists connected to our neighborhood, see our article here.

The name Bushrod Washington (1762-1829) itself may sound familiar. He was the son of Hannah Bushrod and John Washington, John being the younger brother of President George Washington. Bushrod Washington was an associate justice on the United States Supreme Court and died in 1829 in Philadelphia while riding for the circuit court.

1715-1719 Green Street today, formerly the home and infirmary of Bushrod W. James.

West side entrance to the Colonnade

Donor plaques in the Wills Hospital at 9th and Walnut, on the first floor around the corner from the elevators. These have been moved from the first hospital to the second and then to here. Notice the name of architect James H. Windrim in the lower left. His son, John T. Windrim, was the architect for the second Wills Eye building. Also notice the name of George S. Pepper on the left, thirteenth from the top, with the date 1891. That is the year he died and left the bequest of $225,000 that started the Free Library of Philadelphia system, as discussed in our article about the Parkway Central Library here. He also bequethed $12,000 to the Charity Hospital in our neighborhood.

published July 2024